The Failures of Ultimate Explanation

– The Essence of Aristotle’s Arrogance –

The earliest Greek philosophers didn’t really ask ‘what is?’ questions. Rather than quibble over the meaning of words, they tried to solve specific problems by creating bold explanatory theories. And, if critical discussion revealed that an explanation drew untenable or illogical consequences, then they’d try to create a better one.

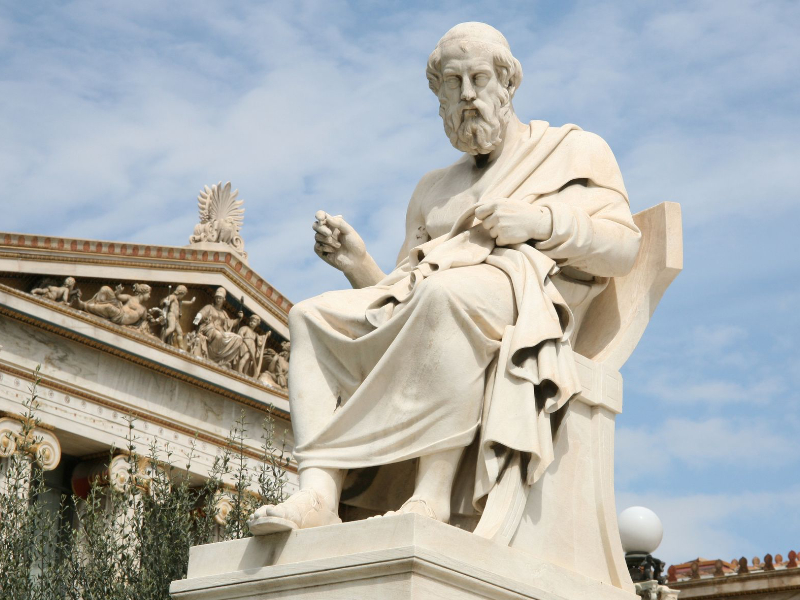

Beginning with Socrates, however, this explanatory approach to knowledge started to fade into a descriptive one. After he recognized that the Ionian’s purely materialistic philosophies failed to account for the consequences of our words, thoughts, and intentions, he turned his gaze from the heavens to the soul — to problems a bit closer to home; to things like justice, beauty, and goodness.

Naturally, then, Socrates became interested in what everything is in and of itself. If, for example, someone claimed that people ought to be happy, he would ask what happiness is, and then watch ’em stumble to describe it.

Description & the Problem of Universals

We all know what things like happiness, heartbreak, and hope are like, but does anyone know what they really are? Is happiness, say, made of some kind of substance? Does it have a shape? Does it exist apart from someone who is happy? What about cars? No two cars are really the same, but we all know what we mean when we say ‘car.’ But, is a car no longer a car if it loses its headlights? Its doors? Steering wheel? What if we got rid of every actual car, would the concept of car still exist? If so, where would it exist? And what would its existence be like?

This is the problem of universals. Socrates’ solution to the problem is: though we can never know what a universal like happiness really is, we can still improve our definition or description of it by criticizing our assumptions.

Socrates’s student Plato agreed that definitions are key. But, because Plato was convicted in Heraclitus’s Everlasting Fire, he thought it was impossible to define anything — the moment you define it, it’ll have changed in the next.

To square the problem of change with the problem of universals, then, Plato argued that universals exist in an eternal and immaterial Realm of Forms — a place where mathematics, numbers, ideas, and other concepts are frozen in perfect form. And those material things which share some characteristic of these forms are in fact just imperfect, decaying copies of the immaterial form.

And we can access this realm, Plato argued, because our souls floated freely through it before they got trapped in our material bodies. We can therefore remember the true essence of a thing through a recollection process, where a teacher questions a student in an attempt to provoke a memory of the object at hand.

Plato’s soberer, though duller, student Aristotle, however, didn’t buy it. To him, Plato’s immaterial realm doesn’t solve the problem of universals. It duplicates it. Form, Aristotle believed, doesn’t exist apart from particular things. To say that Sia and SZA are both women is not to say that over and above them there’s a third thing — woman — to which they’re each related. Rather, womanhood is simply a characteristic they share. And we recognize this shared characteristic because we learn about womanhood through repetition: after examining many women, we eventually discover those similarities that lead us to the true description of womanhood.

Aristotle, therefore, agreed with Plato that we can acquire the true essence of a universal. He just disagreed about how we do it. For Aristotle, we aren’t born with innate knowledge of universals, as Plato believed. But rather we discover them through induction — the repetition of experience, which somehow leads us from particular instances to universals.

The Role of Repetition & Observation

Aristotle’s solution to the problem of universals fails for at least three reasons. First, he completely ignored Heraclitus’s argument — that it’s impossible for any thing to exist in a world of constant change since, the moment you define something, it will have changed in the next.

The second reason Aristotle’s solution fails is due to his belief that repetition can somehow create knowledge. Don’t get me wrong: repetition — or practice — is central to the human learning process, no doubt. But repetition doesn’t create anything new, which the growth of knowledge requires.

Rather, repetition familiarizes and fine tunes an existing solution — one that’s already been created through trial and error. That is, it helps you form habits, which frees up your awareness to focus on new problems. The more practiced we become at a task, the less awareness we require to do it.

Just think, for a moment, about when you first learned to drive or tie your shoes. In neither case, did you produce new knowledge. Someone taught you. And, at first, no doubt both required a lot of attention. But, with practice, more and more were able to accomplish these tasks subconsciously. How long has it been since you put thought into tying your shoes?

The last but not least of Aristotle’s fuck-ups was his assumption that knowledge can be passively imprinted on our minds through observation. This idea was picked up and developed by Francis Bacon during the Scientific Revolution and later defended by John Locke, who said the mind is like a blank slate which is filled by sensory experience.

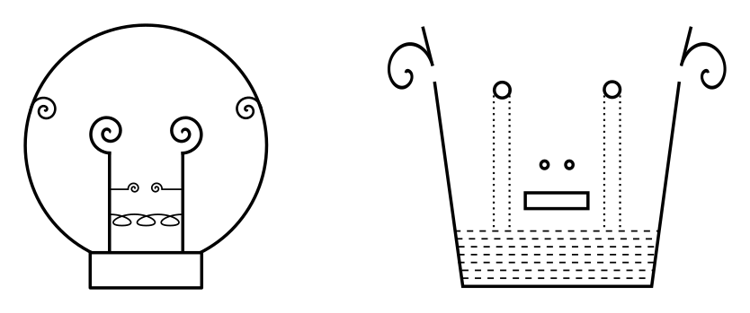

This ‘blank slate’ or ‘bucket theory of mind’, also known as Empiricism, was the mainstream view until finally, in the twentieth century, Karl Popper cleaned up the confusion. But unfortunately, still to this day, I find people falling into its trap. So, let’s get this shit straight.

Despite what Aristotle, Bacon, and Locke believed, and despite what many still believe, it’s impossible to read or infer knowledge from nature. After all, a blank slate can’t do anything. In order to collect data from the world, you need a theory in place to do something with the data — with the 1s and 0s.

Rocks, as you know, can’t do anything with waves in the electromagnetic field. And, further, as you know in this computer and information age, there are many things you can do with 1s and 0s — what software do you need or wanna build?The visual system and a digital marketing software are both conjectural. And each of them are created for a specific aim or to solve a specific problem.

To demonstrate this point — that you need theories in place to catch and use data — Popper would ask his students on the first day of class simply to observe. And after a long, awkward silence, a brave student would finally muster up the courage to say, ‘Um…Professor, what exactly do you want us to observe?’

‘Ah hah!’ Popper would reply, ‘Precisely the point. In order to observe, you must first have in mind a definite problem and hypothesis to guide your observation — to tell you what you seek and where to seek it.’ Charles Darwin also seemed to find this point obvious: ‘How odd it is,’ he states, ‘that anyone should not see that all observation must be for or against some view….’

There’s no escape from it. Every observation is theory-laden. None of your sensory perceptions represent how the world actually is, at least in any complete sense. You don’t, for example, experience the nerve signals traveling from your sensory receptors to your brain as electrochemical wave patterns, which again are just concepts we use to point at, to paint over, some narrow region of reality. Nor do you experience them as traveling through your neurons.

No, instead, you believe they’re out in the world somewhere. But yellow, say, doesn’t really exist ‘out there.’ Rather, your brain creates the experience of yellow through a computational process of electrochemical signals. When you perceive yellow, you’re really detecting a pattern of incoming electromagnetic waves that repeat themselves about 520 trillion times a second. And after they’re captured by a molecule in your eye, the signal is then relayed through a number of biological systems — again, theories — before yellow finally arises in consciousness.

As with all knowledge, your sensory experience of the world is but a web of guesses.

Now, before we put Aristotle’s solution to the problem of universals into its full context, the context of his theory of knowledge, first consider that every experience, every moment, every single thing is projected. And consider further that each of these projections is intimately tied to a complex set of problems — problems that have evolved out of the initial problem of survival and replication, but which now include our hopes and fears, likes and dislikes, anticipations and expectations, memories and beliefs, and much more. And that all these factors, together with our environment, influence how our senses are projected onto experience.

Explanation & the Problem of Truth

Induction is only half the story for Aristotle. And, though induction fails for the reasons provided above, I think it’s still worth our time to hear him out, because the belief that something can be proved positively true haunts the halls of humanity.

Okay, so what’s the other half?

Well, for Aristotle, induction merely gives the premises or concepts which you can then use to deduce the ultimate secrets of the cosmos. The real power for Aristotle, then, lies in deduction. Deduction, Aristotle believed, is the key to demonstrably true knowledge — or epistēmē.

And, hey, can you really blame him? After all, you can’t deny its power. We rely heavily on it to bring order and meaning into an otherwise chaotic and meaningless world. When I tell you ‘I love the warmth you bring into this world,’ it actually means something. But ‘Into warmth I you world this love the bring’ is just noise. Likewise, if two and two equalled anything but four, then we’d be in big trouble, no? And, most importantly, what would become of my Grandma’s oatmeal cookie recipe?!

Logic holds our concepts together; it puts them in relation to one another. Words and concepts, then, have no teeth without it. Concepts need to be put into a thought or an idea or a description — a relational scheme — to mean anything. Logic, or relational properties, are necessary for us to paint stories, pin people with characteristics, build relationships, potter expressions, and choreograph dances. Our words, symbols, and concepts are empty without it.

Okay, so we both agree to some extent with Aristotle — deduction is necessary for thought and communication.

The problem, though, which Aristotle himself recognized, is that, if the key to demonstrably true knowledge is deduction, then our premises or concepts must also be demonstrated. And, if our premises are demonstrated, then they too must have been deduced from something, which in turn must’ve been deduced from something else, and so on.

Well shit! Aristotle thought. How can I get around this infinite regress?

First, he figured that, because words get their definition by convention, they must be true by convention. But this would mean that knowledge is true only by convention, which he didn’t like. So it was here, then, that he turned to induction in hopes of securing conceptual knowledge.

Aristotle’s epistemology, then, relies on both induction and deduction. Once we’ve acquired the true essence of a thing through induction, through the repetition of experience, we’ll have an infallible definition of it. And once we’ve built a big enough dictionary in this way, we should then be able to use our definitions to deduce the ultimate explanation of reality — one that is eternally infallible.

That’s some big talk for a goofy little mammal who burps his own worm. Homie was right on his first go-around — words are created by convention. They’re just noises we make. How, then, can they tell us the true essence of anything? They obviously can’t.

Knowledge is and always will be but a web of guesses, a collection of concepts, or divisions which we arbitrarily paint over the world, over experience, that we put in relation to one another in order to solve our problems and aims.

Conclusion

There is no certainty. No finality. No ultimate truth. There are only our creations. Our guesses. Our mistakes. But, if we are willing to learn from them, willing to carve out our mistakes through trial and error, with deduction as an indispensable tool, a tool to weed out the illogical consequences of our creations, then we can move ever so humbly towards truth.

More Articles

“Poetic Imagination”

I hope at least once in your life you’ve seen the Milky Way. The brushstroke of glimmering white light that cuts through the heavens is breathtaking. And to imagine, before all the light and carbon…

“Carving Knowledge from Our Imaginations”

Every civilization throughout history has created a dogmatic school whose main task is to pass on the doctrine of its founder intact to each generation. In the rare…

“Failures of Ultimate Explanation”

The earliest Greek philosophers didn’t really ask ‘what is?’ questions. Rather than quibble over the meaning of words, they tried to solve specific problems by creating bold explanatory theories…

“Plato’s Moral Tyranny”

Only you, the individual, can decide whether a behavior, norm, or institution is right or wrong. It is your burden and yours alone. You can’t shift it to god, nature, history, or even to society, because whatever…