The Realist

When I reflect back on my life to understand what has motivated me most, that which has really driven me, it is without a doubt truth, or understanding; a commitment to reality. I am a realist in every sense of the word. It’s expressed in my art, in my writing, in my speech, and in my very being.

I simply can’t fathom a life, a point, a purpose, a relationship — or anything else for that matter — without a commitment to reality, to truth. If we’re not oriented to reality, if we’re not honestly and earnestly trying to understand ourselves, each other, and our relationship to the world, then, what are we doing?

“Tell me what am I doing here

If I’m not being real?”

-NF

Now, as both Eastern and Western philosophy have discovered, there are two sides to reality — there is the relative world, the world of appearances, the world of words, concepts, and things, and there is the ultimate reality, the world behind appearances, that which simply is.

One of the earliest to point this out was the ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, who noticed that it was impossible for things to exist in a world of continuous change. “You can’t step in the same river twice,” he said, “for it is not the same river and you are not the same person.” For Heraclitus, then, the Everlasting Fire is all that is, was, or ever will be — it is the Ultimate Reality. And the apparent stability of things is merely an illusion, an illusion that Heraclitus believed is due to a transition in opposites:

Life and death, being awake and being asleep, youth and old age, all these are the same…for the one turned round is the other and the other turned round is the first…. The path that leads up and the path that leads down are the same path…. For God all things are beautiful and good and just, but men assume some things unjust, and others to be just…. It is not in the nature or character of man to possess true knowledge, though it is in the divine nature.

Everything, then, is like a flame — though it appears to have a shape, it is actually just a part of the Everlasting Fire.

Shortly after Heraclitus, there was another Greek named Anaximander, who picked up on the problem of how opposites can exist together — wet and dry, hot and cold, light and dark. If opposites are to exist, he thought, then they must come from and perish into something that is entirely neutral, something indefinite, lacking any particular qualities of its own, not composed of any thing.

He called this no-thing the apeiron, or the unbounded, something like the conservation of the whole in thermodynamics, the equal sign in mathematics, ‘emptiness’ in Buddhism, or the Tao in Taoism.

In short, Anaximander’s apeiron is the Ultimate Reality, free from time, free from space, free from growth and decay, free from birth and death. It is the non-existent that holds the existent. The apeiron or boundless, then, is not only the ever-changing, ever-flowing fountain from which everything ultimately springs, but it is also that no-thing into which everything ultimately fades.

Infinite worlds, Anaximander believed, are created and destroyed here in the apeiron. Anaximander reminds us, though, that because it doesn’t have any qualities of its own, we can only speak of it vaguely. It just is. It is the world that lies forever behind the world of appearances.

[Note: Perhaps not Anaximander but Thales should be credited with this new idea of the boundless. Diogenes Laërtius ascribes to Thales the aphorism: “What is the divine? That which has no origin and no end” (DK 11A1 (36)).]

Like the Presocratics, the Greek philosophers who came before Socrates, the Buddha also believed in a reality behind the world of appearances. Relative truth, he said, consists of the world of things, like justice, rocks, pain, colors, friendship, and anything else you can imagine. Relative truth is exceedingly wonderful, he tells us. It allows us to understand each other, to live, laugh, and labor together. We can use it to share our love, ideas, aspirations, and fears; to build roads, form governments, organize space missions, and to do countless other things.

Relative truth, however, is remarkably deceiving. To see how, examine an object. It can be anything — a thought, a feeling, or something ‘out in the world.’ And as you examine the object, notice how it appears distinct — how it seems to exist on its own, defined by its own essence. Maybe you’re examining a door, and you think it’s a door because it has a handle to open and close some cutout in the wall, creating a portal between one room and another.

Now, examine the object again. But this time I want you to let go of all these words and concepts. Notice that the handle, the hinges, and anything else that comes to mind to describe the object are all just concepts that arise in consciousness; they’re overlayed onto experience. And then, just drop back and simply witness the object, just receive it. If you’ve made it passed the incessant bombardment of thoughts and concepts, you’ll have hit the veil — a place where no further knowledge of the object is even theoretically possible. Here, all you are left with is a wordless experience of it. Here, all you are left with is awe.

In Buddhism, this impenetrable barrier to our knowledge is called the truth of emptiness. It’s not a denial of things like doors, justice, happiness, and other concepts. It’s simply a denial of their independent existence — that they exist apart from the rest of the world, defined by their own essence, that which Aristotle so desperately sought to capture.

Doors, for example, (I don’t know what my sudden fascination with doors is, but let’s stick with it.) don’t just exist on their own, apart from everything else. To build the door, you need a tree. A tree needs rain, soil, and a carpenter to carve the door. The carpenter also needed breakfast, so she could have the energy to carve the door. That means we can’t leave out the grocer and farmer. And the grocer and farmer each relied on their parents going heels to Jesus, as did their parents before them, all the way back to our earliest ancestor. And all these things needed the earth for a home and the sun for energy. And let’s not forget gravity, which keeps us planted on the earth, to say nothing of space. I can’t find a dividing line anywhere. Can you?

Peggy Whitson, who’s spent 665 days in space, has perhaps seen the unity of all things better than anyone. From the window of her aluminum castle, some 250 miles above — or is it below? — the earth, she sees that the earth is one big, blue, ball of delight. A single, interconnected system.

She can watch as the winds carry dust from the Sahara Desert across the Atlantic Ocean to the Amazon basin, where it dumps twenty-seven million tons of rock and minerals every year. And thanks to a fertilizer that is carried in that dust, the trees in the Amazon can flourish. They then suck up water from their roots and release moisture into the air, creating a flying river that flows to the Andes. And as these clouds hit the mountains, releasing rain and snow, the water and ice erode the rock, which is eventually carried into the ocean.

There, waiting for the minerals in that sediment, are organisms called diatoms — single-celled organisms that put more oxygen into the atmosphere than any other source on earth. And if this isn’t enough to show you that all things are connected, just consider that when these little creatures die, they fall like snow and create graveyards on the ocean floors. And over tens and hundreds of millions of years, as the earth’s tectonic plates shift, sea beds rise, ocean levels fall, then some of these graveyards turn into salty deserts, just like the Sahara. Yeah, that special fertilizer I mentioned above — it’s diatom corpses![1]

You can play this world-is-connected game all you want. Seriously, try to separate anything. No matter how hard you try, you’ll see that nothing can exist apart from the rest, defined by its own essence.

The ultimate truth, then, is that the world is one. In the words of the late Tibetan Buddhist lama Kalu Rinpoche, ‘You live in illusion of the appearance of things. There is a Reality. You are that Reality. When you understand this, you will see that you are nothing. And in being nothing, you are everything.’

Like Heraclitus, the Buddha recognized that things only exist in the world of appearances, in consciousness — in the space where perceptions, thoughts, and feelings continually arise and pass away. The Buddha, though, didn’t want anyone to take his claim on faith. No, he encouraged people to connect directly with their experience, undistracted by thought, and discover for themselves the impermanent flow of the contents of consciousness.

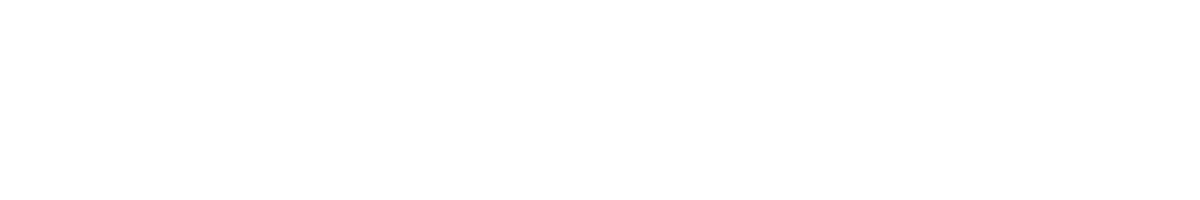

Look for yourself to see whether there’s a persistent carrier of the essence of things? Can you find anything solid; anything to cling to; anything secure? I can’t. When I look, I see only a continuous dance of shapes and colors, of poetry and emotion, of desires and afflictions, all of which are choreographed onto the stage of experience.

When I look directly at my own experience, all I see is Love.

John Driggs | Meditation Teacher & Founder of The Space of Possibility Podcast, Blog, & Retreat Center | Explore & Expand the Space of Possibility that You are!

More Articles

“Poetic Imagination”

I hope at least once in your life you’ve seen the Milky Way. The brushstroke of glimmering white light that cuts through the heavens is breathtaking. And to imagine, before all the light and carbon…

“Carving Knowledge from Our Imaginations”

Every civilization throughout history has created a dogmatic school whose main task is to pass on the doctrine of its founder intact to each generation. In the rare…

“Failures of Ultimate Explanation”

The earliest Greek philosophers didn’t really ask ‘what is?’ questions. Rather than quibble over the meaning of words, they tried to solve specific problems by creating bold explanatory theories…

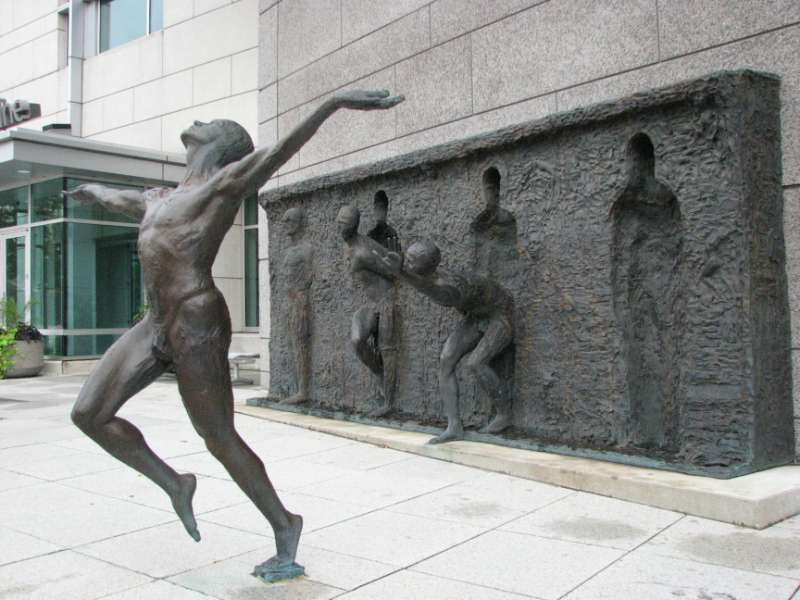

“Plato’s Moral Tyranny”

Only you, the individual, can decide whether a behavior, norm, or institution is right or wrong. It is your burden and yours alone. You can’t shift it to god, nature, history, or even to society, because whatever…