The Four Noble Truths

– What They Are and Why They Matter to You –

The Buddha taught only suffering and its end, which is expressed in the Four Noble Truths — the indispensable foundation embraced by all Buddhist traditions and lineages, no matter how far their metaphysics and methodologies may diverge.

So, what are the Four Noble Truths and why are they applicable to you? That will be the topic of today’s episode.

The First Noble Truth | The Truth of Dukkha

Unlike many philosophers, the Buddha’s entire philosophy was compelled by a simple and noble motivation: he wanted to relieve the world of its suffering. Without understanding this motivation at the root of Buddhism, there is no foundation to stand on; the entirety of the Buddhist path sinks into the sands of inadvertency.

This brings us to the Buddha’s First Noble Truth:

1. Life consists of suffering.

Now, at first glance, this may seem both obvious and, at the same time, too strong. I’m sure I don’t need to convince you that suffering exists and is a part of the human condition (or even the whole of conscious life). You’re likely intimately familiar with it.

But you might hesitate to concede that all life is composed of suffering, that suffering is the essential mark of existence. And I think you’d be right. So, let me take a step back and clarify my terms here. The word ‘suffering’ is a translation from the Pali word ‘dukkha’, but to translate ‘dukkha’ as merely ‘suffering’ would be misleading and incomplete. ‘Dukkha’ is a much broader and more encompassing term than ‘suffering’ alone.

The problem with the translation here is that modern English words are too specialized, too limited, and too strong. We therefore can’t capture the full meaning of dukkha with a single word, so we’ll need to call in some other concepts to help point us to the actual felt experience of dukkha itself. From here you can then begin to build your own direct understanding of dukkha.

If we look at the word ‘dukkha’ etymologically, we can break it into two parts: the prefix ‘du’, which means ‘bad’ or ‘difficult’, and the root ‘kha’, which generally means ‘empty’ but can more specifically mean ‘the empty axle hole of a wheel.’ So, if we put these two words together, we can begin to feel more viscerally what is meant by ‘dukkha’ — just imagine riding in a cart that has a poor fitting axle. It’s going to be a bumpy ride.

We can think of ‘dukkha’, then, as the bumps and agitations, the ups and downs, the felt experiences of our journey through samsara — the wheel or cycle of life, of birth and death, of pleasure and pain, happiness and sorrow, gain and loss, praise and blame, fame and disrepute.

This dramatically changes and enlarges our understanding of the First Noble Truth. But let’s not stop here. Let’s look at the more general meaning of ‘kha’, empty, to add another dimension to our understanding.

When we look at ‘dukkha’ from this angle, we can think of it as anything that is ultimately empty of satisfaction, anything empty of permanence or lasting peace. We can translate ‘dukkha’ more generally, then, not as ‘suffering’ but as that which is ultimately unsatisfying or unreliable, which is all things in a world of constant change.

Okay, now that we hopefully have a clearer picture of ‘dukkha’, let’s consider why this knowledge or understanding is applicable to our own lives.

The first thing to say, perhaps, is that you can’t be freed from dukkha — the bumpy ride — until you understand what it is that is causing the bumpy ride. To float smoothly through life, to find lasting peace, harmony, and tranquility, you first need to witness directly the dukkha in your own life so that you can transcend it.

Understanding dukkha, however, is not only the gateway to liberation, to freedom, to the highest peace, but it is also a direct path to compassion — the heart-felt desire to free ourselves and others from suffering. It is precisely our deepening understanding, our deepening experience, of dukkha that opens us and moves us naturally toward compassion.

So, how can we start opening to dukkha?

With mindfulness. It is mindfulness, which the Buddhist practice vipassana or insight meditation seeks to cultivate, that allows us to open to life, to dukkha. It is mindfulness that allows us to get close to it, to let it in. It is mindfulness— the wide open and all-encompassing heart of awareness — that listens to dukkha, that tries to understand it, that strives to love it. It is mindfulness that opens us to the direct experience of the First Noble Truth.

If you aren’t already committed to a mindfulness practice, I encourage you to begin one today. Don’t wait to open to and transform the suffering in your life. [I offer all my meditation courses for free, including a 30-day introduction to vipassana or insight meditation, a 2500-year-old Buddhist practice that seeks to cultivate mindfulness.]

The Second Noble Truth | The Cause of Dukkha

Once we start opening to dukkha, we can then begin to see that it, like all things, is brought about by causes and conditions, which brings us to the Second Noble Truth:

2. Craving is the Cause of Dukkha

Before we continue, let me just remind you that these truths are not dogmas to be accepted on blind faith. The Buddha invites us to explore these truths in ourselves, to accept them only after we have earnestly and honestly investigated them in our own experience (and even then he asks us not to cling to them).

With that said, to better understand this Truth, let’s first seek some clarity of the term ‘craving’ by looking at the Pali translation and, then, brushing away some confusion the translation creates. So, the Pali word for craving here is tanha, which I think is a good translation. But, to add some depth and dimension to it, the etymology also points us to the term ‘thirst’ at its root, which I think really helps to capture the feeling of this mind-state.

Now, where things can get confusing is that tanha is also often translated as ‘desire’, which is a bit too broad. We sometimes use the word ‘desire’ to simply state our intention to do something (e.g., I desire to study eastern philosophy in college), which is not necessarily tanha.

Desire in this way, or even in itself, is not bad. It’s not the root of suffering. In fact, it’s necessary. We need desires to move us through the world and keep us interested in it. We need desires to live and learn and grow. You wouldn’t be reading this now if you didn’t have some desire to do so.

‘Desire’ in a Buddhist context, then, is narrower. We must look deeper into the desire to see if there is any self-attachment, any grasping, any identifying with the desire.

Something I’ve found helpful in my own practice is to look at desires (people, objects, beliefs, mind-states) in terms of addiction. Which desires can I simply enjoy in the moment without grasping to and which desires strip me of my freedom? Are there any desires for which I don’t have a choice?

To explore where craving shows up in your own life, it may also be useful to look out for desires in your life through these categorical lenses: (1) the desire for sense pleasures, (2) the desire for existence, or becoming, and (3) the desire for non-existence, or non-becoming. Let’s take a look at each of these in turn.

The Desire for Sense Pleasure. It’s important to understand that, in the Buddhist frame, the mind is considered the sixth sense, so all mind-states and emotions are included here as objects of our sensual desire (joy, rapture, excitement, concentration, calm, etc.).

With this in mind, it may be useful now to ask yourself the same question the Buddha asked during his search for Awakening — “What is the gratification in the world?” Now, of course you’ll have to answer this question for yourself but what the Buddha found is that gratification comes from joy and pleasure.

If you consider your own life, where are you seeking joy and pleasure? How do you seek gratification? For many people, the standard model of operating is to find happiness and pleasure through our senses. We constantly try to fulfill ourselves through sex, food, movies, shows, music, popularity, affection, esteem, drugs, and even ‘peak’ spiritual experiences.

Many people go through their whole lives just seeking one hit of pleasure after the next, and then they die. This road has been tried through and through with little success, yet where do so many of us continue to seek happiness?

The Buddha then asked the interesting follow up question, “What are the downsides or drawbacks in the world?” And he saw that nothing lasts, that nothing is permanent, that everything is constantly in flux.

If we consider this in the context of sense pleasures, we see that there is no possibility of acquiring lasting gratification or happiness, because our sense pleasures never last. In fact they’re often incredibly fleeting, lasting only a moment. Trying to fulfill yourself through sense pleasures is like trying to quench your thirst by drinking salt water — the more you drink, the thirstier you become.

The Desire for Existence, or Becoming. This dimension of craving is a strong one in the Western world. There is so much pressure in our culture to ‘become’ someone, to do something great and meaningful with our lives. It’s as if our worth is entirely dependent on what we produce, on who we become, on what titles we acquire, on what job we get, on what car or house we buy.

It’s always go, go, go, do, do, do. And so we often get stuck in the planning mind, where we obsessively plan and try to control and map out everything. We obsess over future versions of ourselves and our lives to the point where we are never really able to arrive here in the moment. It’s as if we’re always leaning into the next moment, into the next experience, the next feat, the next thing.

Joseph Goldstein calls this ‘the in-order-to mind’. We’re with this moment in order to get to the next. I’m going to school in order to get a well-paying job. I’m at this job in order to get a nicer car and home. I’m going to church or following these rules in order to get into heaven.

Or you can also think of it as the if-then mind. If only I had this much money, then I’d happy. If only I had a better body, then I’d be satisfied. If only x, y, or z, then I’d be complete.

Can you see how this is a problem? We can’t hang our happiness out in front of us, always out of reach.

The Desire for Non-Existence, or Non-Becoming. Finally, there is the desire for non-being, which can be thought of as aversion—turning or pushing away from the unpleasant with ill-will, wishing that it would go away.

We can see this with emotional states like depression — e.g., life is so bad, I don’t want to be alive–and physical pain. But what is important to note here is that this kind of desire is still rooted in the sense of self. The ego builds itself up by identifying with or attaching to the unpleasant.

* * *

As you go about your week, I invite you to start opening awareness to all the desires in your life; start making notes of them. And in particular, try to notice how much of your time and attention is oriented toward sensual desires.

And when a desire arises, don’t hide or distract yourself from it, but rather really bore into it — examine the raw experience of it. Explore every inch of it with compassion and interest, with a real eagerness to understand it. And if you’re able to observe a desire without reacting to it, pay careful attention to that moment when the desire subsides? What is that moment like?

And if you do end up getting pulled in by an unskillful desire or end up acting on one, no worries. There’s no need to judge yourself. Remember, judgment is just another thought. Instead, open awareness again to the present moment’s experience, try to note how your mind and body feel, apologize if necessary, and consider whether the desire delivered on its promise.

Remember, what we’re really seeking to cultivate here is wisdom — we want to know from our own direct investigation what leads on to peace, happiness, and freedom, and what does not.

* * *

The Third Noble Truth | The Cessation of Dukkha

Once we can start to witness directly how craving leads to suffering or dissatisfaction in our own lives, we naturally begin to see an alternative, which brings us to the Third Noble Truth:

3. The absence of suffering, wellbeing, is possible

There is one thing all Buddhists agree on, one belief in which all traditions converge: the understanding of what liberates the mind — that dukkha is brought to an end through non-clinging, through letting go. Every practice, then, in Buddhism must be understood to work towards this purpose — freedom.

“This holy life does not have gain, honor, and renown for its benefit, or the attainment of virtue for its benefit, or the attainment of concentration for its benefit, or knowledge and vision for its benefit, but it is this unshakeable deliverance of mind that is the goal of this holy life, its heartwood and its end.” — The Buddha

Okay, so how does one let go? Well, this gets us into the Fourth Noble Truth, which is the path leading to the end of suffering, but because the Fourth Noble Truth contains so much substance, I will save that for another day.

Today, however, I will push you in the general direction of awakening, first, by sharing three qualities of experience or reality for you to investigate for yourself and, second, by providing you with free meditation practices.

The Three Qualities. Okay, the first of the three qualities I invite you to begin to open and refine awareness to is the changing nature of all phenomena. We all know that everything changes, but a conceptual understanding isn’t enough here. It is when we see directly in our own minds the impermanence of all things that true transformation happens. When we look with wisdom at our experience and see that everything in it is changing so quickly, we realize directly that there is nothing to hold onto, and so eventually the mind lets go of clinging.

The next thing to investigate is the selfless nature of experience, the selfless nature of all phenomena. This, when contemplated, should naturally arise from seeing clearly the ever-changing flow of experience. When you look, you will see that there is nothing that lasts long enough to be called ‘self’, ‘I’, or ‘mine’. Instead, you’ll see everything as a continuous, interconnected process.

But if you continue your investigation, you will also discover that all things arise out of certain conditions. Just consider: you didn’t pick your genes, you didn’t pick the family and culture you were born into, you didn’t pick your trials and hardships, those people and events that carved your character. Everything about you, including your own volitions, is a product of the rest of the world around you.

One way to think of this is to imagine a rainbow. A rainbow is selfless. When we look for it, there is no one thing called rainbow. There is air, moisture, light, a visual system, and consciousness. And when the light is reflected at a 45 degree angle from the sun, to the moisture in the air, and back into the eye, then we see what we call ‘rainbow.’ Each moment’s experience is akin to this: a collection of causes and conditions.

Another way to think about it is to imagine a plant. When we look deeply into a plant, we actually don’t see a plant. We see soil, water, air, and sunlight, we see the creatures that fertilized and pollinated the plant, we see the earth and the space and gravity that hold it together. When we look closely at anything, we see that everything simply inter-is. This is seeing with wisdom, seeing without the delusion of a separate self entity who has its own will and force that is separate from the rest of existence.

Finally, the last thing I encourage you to investigate for yourself is what I already spoke about above — that is, dukkha: the dissatisfactory and unreliability of all things. Really get to know how dukkha presents itself in your experience.

Meditation Practices

Course 1: Cultivate Mindfulness. Only when I am mindful — connected directly to experience, open to it, interested in it, not lost in thought — can I wisely navigate this Space of Possibility, can I truly understand and, therefore, love my friends and family.

Course 2: Love & Understanding. In this course, you will get to know Love directly. Not conceptually, but experientially. Come cultivate the capacity to carry Love with you in all places and at all times. Let love become what you are.

Course 3: Know Your Shadow Self. Do things feel off? Are you connecting well to others or to yourself or to the present moment’s experience? Are your emotions dry and unfeeling or in extreme turmoil? See and accept your shadow. Know freedom.

Habit Builder. If you’re finding it difficult to show up for your meditation practice, use this course to slowly build out a habitual space to house your formal practice. Get comfortable with the silence. Learn to sit with yourself.

“If you let go a little, you’ll have a little happiness. If you let go a lot, you’ll have a lot of happiness. If you let go completely . . . you’ll be completely happy.” — Ajahn Chah

The Fourth Noble Truth | The Path Away From Suffering

As I said above, I will get into the Eightfold Path — the path that leads to the end of suffering another time.

Thanks for reading,

John Driggs | Meditation Teacher & Founder of The Space of Possibility Podcast, Blog & Retreat Center | Explore & Expand the Space of Possibility that You are!

More Articles

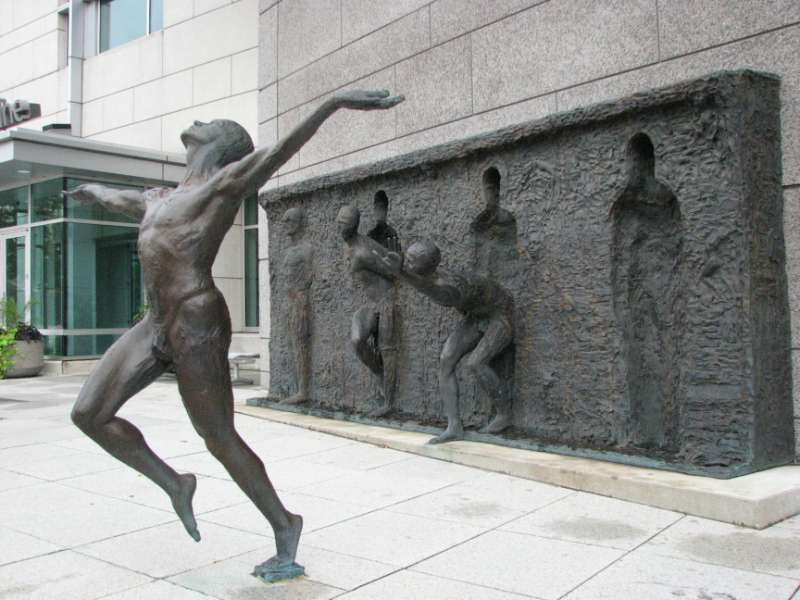

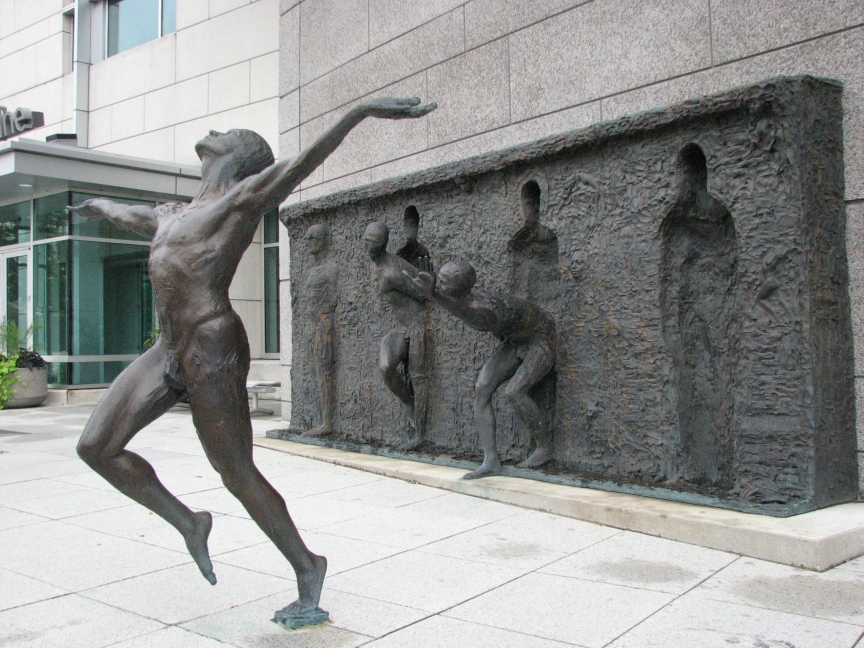

“Poetic Imagination”

I hope at least once in your life you’ve seen the Milky Way. The brushstroke of glimmering white light that cuts through the heavens is breathtaking. And to imagine, before all the light and carbon…

“Carving Knowledge from Our Imaginations”

Every civilization throughout history has created a dogmatic school whose main task is to pass on the doctrine of its founder intact to each generation. In the rare…

“Failures of Ultimate Explanation”

The earliest Greek philosophers didn’t really ask ‘what is?’ questions. Rather than quibble over the meaning of words, they tried to solve specific problems by creating bold explanatory theories…

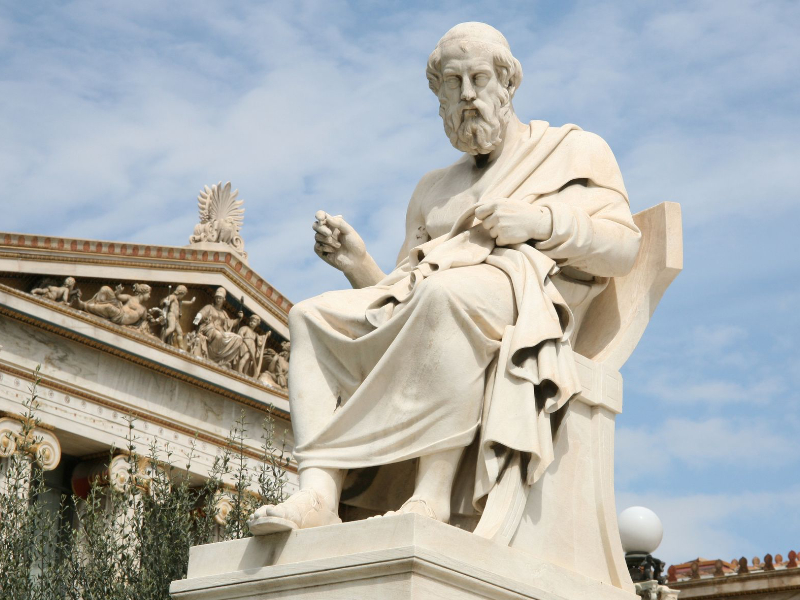

“Plato’s Moral Tyranny”

Only you, the individual, can decide whether a behavior, norm, or institution is right or wrong. It is your burden and yours alone. You can’t shift it to god, nature, history, or even to society, because whatever…