The Impulse for Freedom

– The Soul’s Search for Truth, Beauty, & Goodness –

We have seen how the Greeks came to better understand the physical world, as well as abstract concepts like happiness. But we haven’t really asked if and how we can come to better understand our own morality. Can we make objective claims about our values, aims, behaviors, traditions, and institutions? Is there anything like moral progress? How can we be sure?

Moral philosophy is arguably the most confused and misguided area of study in philosophy. On the one side, there are still many who believe that morality doesn’t belong to the sphere of science and reason. It belongs to religion, they argue. Only god can determine what is right or wrong or good and evil.

And on the other side, there are many philosophers and scientists who claim that there can be no objective truths in morality. They often cite the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher David Hume who argued it is impossible to derive an ought, or a moral proposition, from an is, a factual statement. “’Tis not contrary to reason,” he famously wrote, “to prefer the destruction of the whole world to the scratching of my finger.” This view, which is becoming increasingly popular on the political Left, claims that our values and behaviors have no objective basis but depend entirely on the culture we grow up in.

Were philosophy confined to old men in tweed jackets, this wouldn’t be much of a problem. But ideas are powerful and they can have drastic consequences. For those who believe morality comes from god, there is the obvious problem of suicide bombers, sexism, patriarchy, homophobia, forced marriages, genital mutilation, racism, mass genocide, and all the rest that are brazenly forced onto society.

And in the other camp, we are left with the absence of any rational moral theory or framework. Morality amounts to nothing more than a fiction. For these moral relativists, we in the West have no place to stand to tell the Taliban it is wrong to stone their daughters for having sex before marriage. We can never tell the Saudi Arabian government it is ‘wrong’ to hang gays in the street by the dozens. Why? Because we in the West don’t share the same values as the Taliban or the Islamic Theocracy of Saudi Arabia. So much for spreading political freedom, freedom of speech, women’s equality, and other basic human rights to the world’s precious children.

Moral relativism is not only misguided. It’s irresponsible, cowardice, and downright cruel. Until recently, though, it didn’t have much teeth, since most people still looked to their religion on matters of morality. As more and more of us leave religion behind in this Information Age, however, the danger of collapsing into moral relativism is becoming more imminent and the need for a secular and rational morality more pressing.

In this episode, then, we will explore the problem and hopefully clear up the confusion. For there is a simple one on offer, which to my surprise has been largely overlooked by philosophers, scientists, and intellectuals alike. The solution is this: all knowledge — philosophical, physical, biological, genetic, individual, social, political, and moral knowledge—evolves through the same humble method of trial and the elimination of error.

In the field of morality, then, Hume’s problem disappears. We can concede that it is impossible to derive an ought from is. But that’s no matter since all of our knowledge is conjectured anyway, including our values and aims — what we ought to do.

This, however, does not mean we are forced to abandon our pursuit of moral knowledge or progress. Consider a child’s aim to become a doctor when she grows up. Could she be wrong about this aim? Yes, of course. We all have experienced something like this, where we thought we wanted something but ended up being wrong about what we wanted. The very fact that we made an error, though, suggests there are objective facts about the moral landscape [Space of Possibility].

So, is moral progress certain? No. Just like scientific knowledge, which is composed of bold theories, highly fallible human inventions, we can be wrong about the direction we’re heading in the moral landscape [Space of Possibility]. But again, just as in the physical sciences, the solution isn’t to abandon reason and say that all theories are equally unfounded, that Thale’s theory of earthquakes is no more or less tenable than the elastic rebound theory of plate tectonics, like the moral relativists do with our behaviors or norms.

No, the solution is to do more science — produce more creative theories that we can subject to critical discussion, observation, and experiment. When the now-woman figures out that she does not want to be a doctor, she has to put forward another idea about what she wants and then submit the idea to critical pressure — she can discuss the pros and cons, weigh them with her other values and interests, and give it a try. And of course, she may be wrong again. But by applying critical pressure to each theory, she will continue to learn, she will continue to chip away at her mistakes.

When we own up to our fallibility in the moral sphere, when we admit that not only our behaviors, norms, and traditions but also our values and aims are conjectured, then we can work openly and honestly to move toward a better world, toward a better life, toward a better experience.

This is what the Ancient Athenians did when they established the first free and open society, under the leadership of Pericles. Let’s see how they got there.

Rites, Rituals, & Traditions

Before cultures clashed, our social behaviors — rituals and traditions — would have seemed as natural as the seasons: each controlled by the gods, or nature. So, there wasn’t really reason to question the social structures and cultural dogmas that had evolved.

Some five hundred years before Christ, though, as cultures near the Mediterranean expanded and clashed, people were finally given reason to question whether god — or nature — had a monopoly on social structures, traditions, rituals, and behaviors.

The Persian King Darius I (550–486 BC), for example, in a rather inspired moment of teaching and, no doubt, to mess with some Greeks living under his rule at the time, asked the Greeks how much money it would take to convince them to eat the flesh of their fathers when they died.

The Greeks, whose custom was to burn their dead, freaked out and said no amount would convince them. So, King Darius called over the Callatians, whose custom was in fact to eat their dead, and asked them how much money it would take to persuade them to burn their dead. They too freaked out and asked why he would suggest such a thing. ([1] Herodotus, The Histories)

Natural vs. Social Laws

Whatever the effect was on Darius’ subjects, there was one Greek who learned a great deal from these culture clashes. Growing up in a city under the control of Darius’ son Xerxes, Protagoras (c. 490 — c. 420 BC) witnessed firsthand the clash of beliefs, norms, and traditions from those cultures that had been swallowed by the Persian empire. And it led him to conclude that our social norms and behaviors are quite different from natural laws. Social norms, he argued, are created and enforced not by god — or nature — but by each of us.

Social norms are created and enforced not by god — or nature — but by each of us.

This had dramatic consequences because it shifted the burden to distinguish between right and wrong from god — or nature — to each individual. Only you, the individual, he claimed, can judge whether a behavior, norm, law, or institution is right or wrong.

The burden is yours and yours alone. You can’t shift it to god, nature, history, or even to society. Because, whatever authority you accept, it is still you who must accept that authority.

What a shift in thought!

Heavy, I know. But, heavy as it may be, this ability to paint over the world with our own morals is, I agree with Protagoras, incredibly motivating and inspiring.

Just think: unlike our critter friends, who’re confined to the narrow range of behaviors that natural selection has carved out for them, you and I can radically change our behaviors once we’re aware of them. And, what’s more, we can now even change our genes!

We can ask what problem a behavior or gene is meant to solve, and then, with a healthy dose of creativity and criticism, we can improve our solutions. And even more impressive, if after a long and critical discussion we think the problem a behavior or gene is intended to solve is objectionable, then we can toss the problem or gene altogether. (Let’s proceed here, however, with caution — we don’t need another eugenics epoch.)

So, unlike the other animals and unlike all those who came before Protagoras, your morality is up to you.

The Space of Possibility is yours. And it’s wide open.

You wanna paint a thought onto canvas or express an emotion with a cello. What about start a punk-rock band or dress up in drag? You wanna parachute out of an airplane? Take up tap-dancing or design a fashion label? What about build a computer or write the code for a virtual dream world? Wanna find yourself laying on your back in Goblin Valley, munchin’ on some magic shrooms, gazin’ up at the heavens in awe? Or maybe you wanna pull an Elon Musk and plan a trip to Mars?

The Space of Possibility is endless! So, start exploring it now.

Just remember to course-correct as you go. Continue to adjust both your aims and solutions, your will and way, as you communicate honestly with experience, as you learn from it, as you chip away at your mistakes.

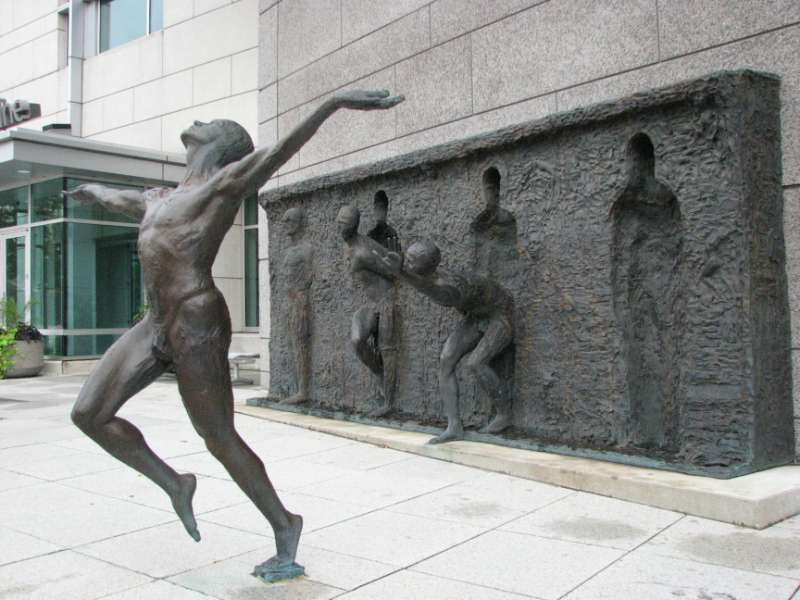

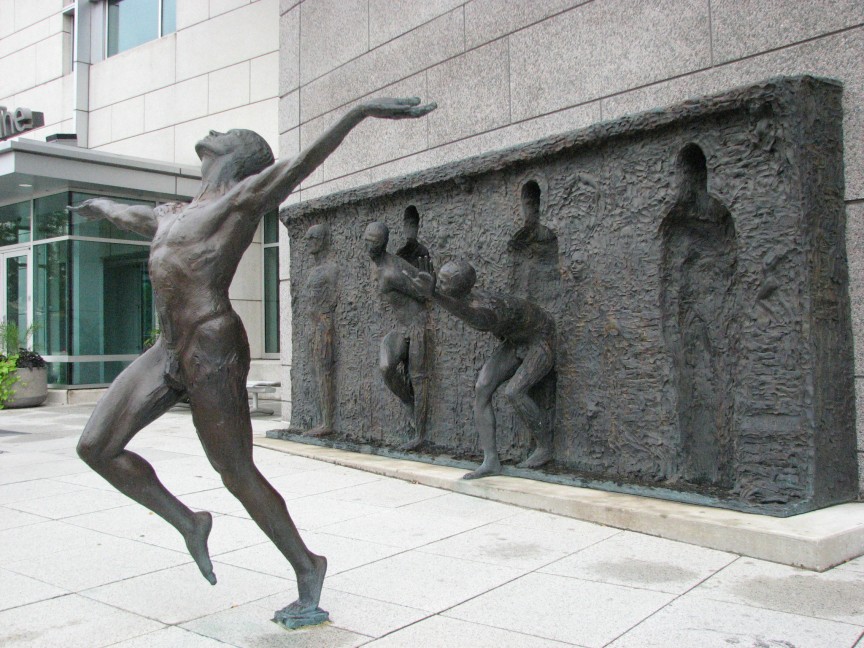

The Birth of Individual Freedom

Socrates (c. 470–399 bc) is the symbol of this wisdom. In masterful displays of irony, he would lead people to their ignorance — to the infinite space beyond the Wall — by asking questions that highlight clashes in one’s own beliefs, morals, and assumptions.

He spent his days questioning people about things like justice, goodness, and beauty. And in the end, he even gave his life to defend the right to do so.

Looking for a scapegoat to blame for Athens’ misfortune in the Peloponnesian War, the jury sentenced Socrates to death for corrupting the youth and undermining the state religion.

Had he apologized, he probably would’ve been exiled. But Socrates refused to abandon reason. ‘To put it bluntly,’ he tells the jury, ‘I’ve been assigned to this city as if to a lazy horse who is in need of a great stinging fly. All day long I will rouse and criticize every last one of you.’ Not flattered, the jury poured Socrates the hemlock.

Socrates wasn’t stupid. He understood the consequences of his provocation. But to him, the unexamined life isn’t worth living. Reason, he believed, is what makes us human — it is the divine spark; the spirit of progress; the path to truth, beauty, and goodness. So, he courageously gave his life to defend it.

Nor was Socrates an enemy of democracy, as some believed. Rather, he criticized Athens as any responsible democrat should — to find holes in the state’s laws and institutions in order to clear the way for a better life, in order to find truth, beauty, and goodness. He understood that a democracy is the only system of government that allows people to reform their institutions with reason rather than bloodshed.

And he also understood that democracy itself can’t provide reason. Only individuals can. It wasn’t the Athenian democracy that turned its back on reason and sentenced him to death. It was the people. Governments and institutions are merely fictions that live in the minds of individuals. They have no existence or power apart from us.

The responsibility to engage in reason, then, will always lie with the individual. The heavy lifting is on you to build a better life.

Democritus (c. 460 — c. 370 bc), the atoms and the void guy, was also an individualist. He believed each of us carries the burden to create a better life for ourselves.

He believed that every person is a little world of her own. Only the individual can suffer. Only the individual can feel love, joy, and happiness. It is up to each individual, then, to put social laws and institutions into place. It’s up to each of us to judge and improve them. And, if necessary, it’s up to each of us to defend them.

Pericles (c. 495–429 bc), the general of Athens at its peak, took this burden seriously. Before him, Athens was essentially an oligarchy in all but name, since the aristocrats still held all the wealth. To even out this imbalance, then, Pericles created the first civil project in history — a state-sponsored economic incentive to inspire all of Greece.

‘We will build all kinds of enterprises,’ he declared, ‘to provide inspiration for every art and to find employment for every hand.’ True to his word, the project was a success. It created many jobs for the middle and lower classes and produced art that is still admired today. He also introduced state salaries for jurors and soldiers. And even used the state treasury to pay for the occasional public festival.

Pericles believed that the whole of Athens was an education. It doesn’t compete with other nations. It sets an example. And, so it did. Under the influence of the great thinkers of Pericles’ generation, Pericles and his fellow Athenians not only created a world empire. They implemented the world’s first open society — a society whose values are sketched out beautifully in a speech he gave at the end of the first year of the Peloponnesian War:

“The laws afford equal justice to all alike in their private disputes, but we do not ignore the claims of excellence. When a citizen distinguishes himself, then he will be called to serve the state, in preference to others, not as a matter of privilege, but as a reward of merit; poverty is not a bar. The freedom we enjoy extends also to ordinary life; we are not suspicious of one another, and do not nag our neighbor if he chooses to go his own way…But this freedom does not make us lawless. We are taught to respect the magistrate and the laws, and never to forget that we must protect the injured. And we are also taught to observe those unwritten laws whose sanction lies only in the universal feeling of what is right [-this is the goodness inside each of us that Socrates tried to point us toward-]…And although only a few may originate a policy, we are all able to judge it. We do not look upon discussion as a stumbling block in the way of political action, but as an indispensable preliminary to acting wisely…We believe that happiness is the fruit of freedom and freedom that of valor….”

Pericles’ words symbolize the commitment of a new generation — a commitment, not to the gods or to the state or to a specific group, but to the individual. It is a commitment to freedom — the freedom to express one’s self; the freedom to distinguish between right and wrong for one’s self; the freedom to vote for one’s political leaders; the freedom against institutional prejudices and biases; the freedom against unwanted physical force; and the freedom to go your own way if you so choose.

Conclusion

Without political and personal freedom, without a governmental system built around the individual, how will Love — truth, goodness, and beauty — freely and openly express itself?

Let us turn our gazes inward, as Socrates did, to the soul, to find a foundation for our laws and institutions, to build and conduct our communities. Our political motivations should not and cannot be framed around the state, the dollar or the economy, or any other fiction. They must find themselves rooted in the free individual — the only place where truth, beauty, and goodness, or anything else for that matter can exist, can breath, can express itself.

“Know your Self” — Socrates

And keep in mind that freedom does not come free. As the great thinkers of Pericles’ generation stressed, only you can build these freedoms into our institutions. Only you can criticize and improve them. And, if necessary, only youcan defend them. Nature, god, and society cannot do this for you. The future depends on you. The burden is on you to build a better future, to build a better life, to build a better world.

More Articles

“Poetic Imagination”

I hope at least once in your life you’ve seen the Milky Way. The brushstroke of glimmering white light that cuts through the heavens is breathtaking. And to imagine, before all the light and carbon…

“Carving Knowledge from Our Imaginations”

Every civilization throughout history has created a dogmatic school whose main task is to pass on the doctrine of its founder intact to each generation. In the rare…

“Failures of Ultimate Explanation”

The earliest Greek philosophers didn’t really ask ‘what is?’ questions. Rather than quibble over the meaning of words, they tried to solve specific problems by creating bold explanatory theories…

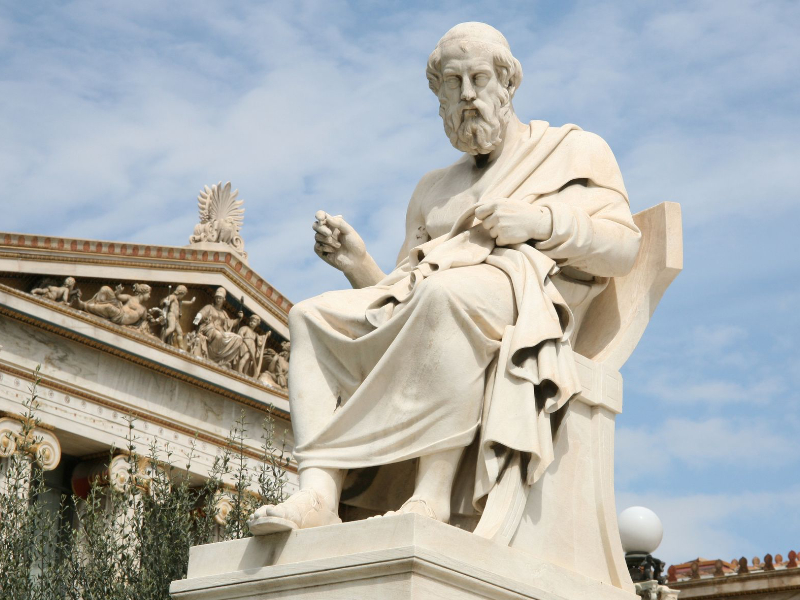

“Plato’s Moral Tyranny”

Only you, the individual, can decide whether a behavior, norm, or institution is right or wrong. It is your burden and yours alone. You can’t shift it to god, nature, history, or even to society, because whatever…